3.1 The Big Bang Theory and Alternative Models

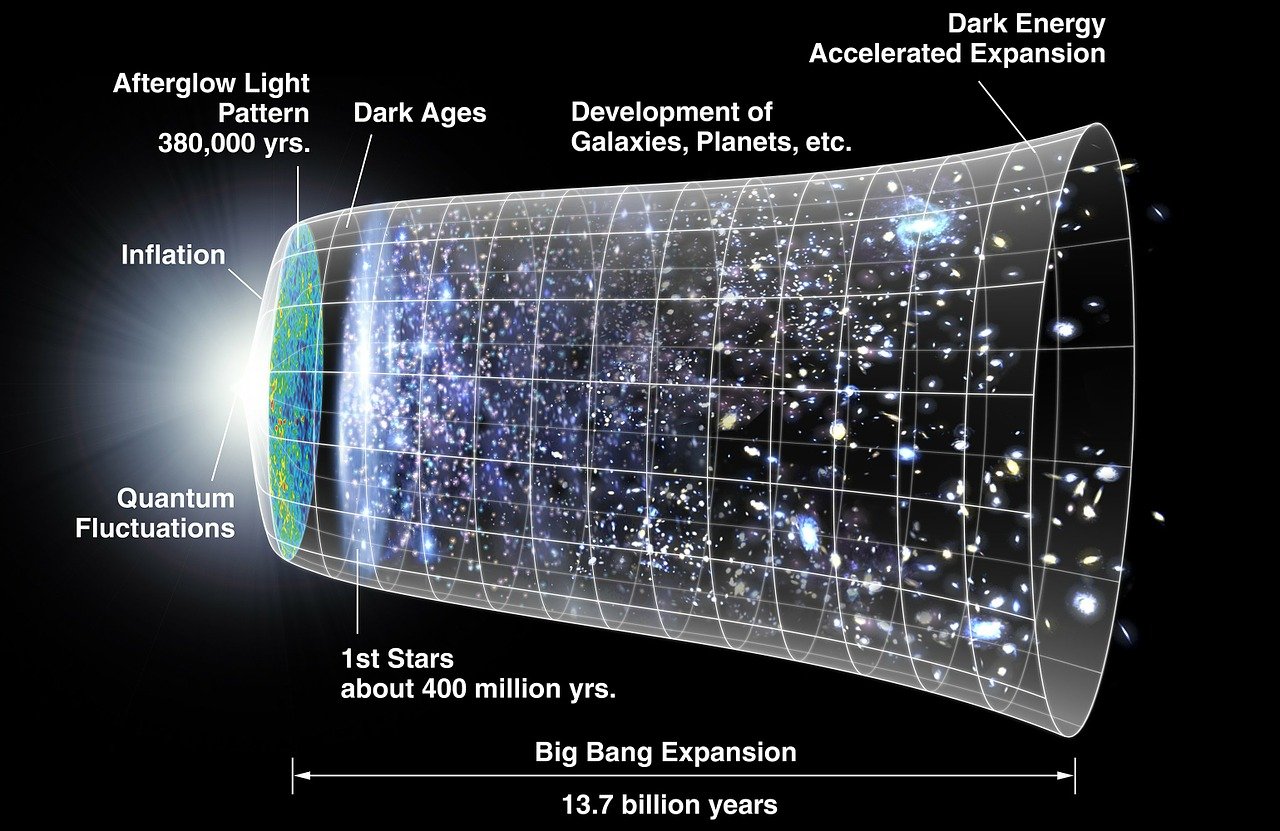

Since the beginning of the 20th century, a series of major scientific discoveries has profoundly transformed our understanding of the universe. Moving away from the idea of a static and eternal cosmos, astronomical observations — notably Edwin Hubble’s measurements of the redshift of distant galaxies — revealed that the universe is expanding. This discovery led to the development of the Big Bang model, which describes the universe as having evolved from an extremely hot and dense state approximately 13.7 billion years ago 1.

Today, the Big Bang model is widely accepted within the scientific community and is supported by several independent lines of observational evidence, such as the cosmic microwave background and the relative abundances of light elements. However, it has not gone unchallenged. Alternative cosmological models — including steady-state theories and various cyclic or bouncing scenarios — have been proposed, often motivated by conceptual concerns about an absolute beginning or by attempts to address unresolved questions within the standard model.

In this section, we will examine both the Big Bang model and its main alternatives by evaluating the motivations behind each proposal, the phenomena they seek to explain, and the strengths and limitations they encounter when confronted with current observational data. Our aim is to clarify why certain models have gained broader acceptance, while others remain active areas of theoretical exploration.

This comparative approach will allow us to better understand both the success of the Big Bang framework and the reasons why the question of the universe’s origin remains an open and intellectually active field of research.

The Early Days of the Big Bang Theory #

Albert Einstein and General Relativity (1915)

- In 1915, Albert Einstein published the theory of general relativity — a new way to describe gravitation, not as a force but as the curvature of spacetime produced by mass and energy. His equations implied that the universe is dynamic: it must either expand or contract.

- Uncomfortable with that conclusion (he believed the universe was static), he introduced the cosmological constant, a mathematical term to prevent collapse or expansion. He later called it his “greatest blunder,” even though a modern version of the cosmological constant (dark energy) has been reintroduced to explain the accelerated expansion.

Alexander Friedmann and Georges Lemaître: the expanding universe (1920s)

- 1922–1924: Russian physicist Alexander Friedmann published solutions to Einstein’s equations showing that the universe can expand or contract. He demonstrated mathematically that a static universe is not the only option.

- In 1927, Belgian priest-physicist Georges Lemaître built on these solutions and connected them to observations: he proposed that the universe is expanding and began in an extremely dense, hot state — later dubbed the “primeval atom.” He established the distance–redshift relation and derived an expansion constant.

- An important nuance: Lemaître did not use a “radiation rate” to measure this expansion; he relied on galactic spectral redshifts and distance estimates.

Their theoretical work provided the conceptual footing for the Big Bang model.

Observational Evidence for the Big Bang #

Several independent observations support the picture of a universe that was once much hotter and denser and has been expanding for billions of years.

Expansion of the universe — the Hubble–Lemaître law

- In 1929, Edwin Hubble observed that the farther away a galaxy is, the more its light is redshifted (relation v = H₀ d). He combined distance measurements (Cepheids, and later other indicators) with velocities (spectral lines).

- What does this redshift mean? The wavelengths are stretched because space itself is stretching — not merely a classical Doppler effect in a fixed space.

“Fossil radiation” — the cosmic microwave background (CMB), a thermal relic of the young universe

- Prediction (1948): Ralph Alpher and Robert Herman (with George Gamow) predicted a radiation field of a few kelvins, released when the universe became transparent ~380,000 years after the beginning.

- Discovery (1965): Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson detected an isotropic microwave “noise” at ≈ 2.7 K, exactly as predicted.

- Precision measurements: The COBE satellite (1989–1992) measured an almost perfect blackbody spectrum (2.725 K) and tiny anisotropies (~10⁻⁵). WMAP and then Planck mapped the fluctuation spectrum (acoustic peaks), allowing precise estimates of the universe’s age, matter content, curvature, and more.

- Why this is crucial: These tiny temperature variations are the seeds that, under gravity, grew into galaxies and clusters.

Light-element abundances — the young universe’s “chemical recipe”

- When? From ~1 second to ~3 minutes after the Big Bang, temperatures exceeded 10⁹ K. Protons and neutrons fused primarily into helium-4 (≈ 24–25% by mass), with a little deuterium (~few × 10⁻⁵), helium-3, and lithium-7.

- What we observe: In nearly pristine environments — quasi-primordial gas clouds and ancient, metal-poor stars — measured abundances match the calculations of primordial nucleosynthesis remarkably well. A mild “lithium tension” remains: observed Li-7 is lower than the predicted value.

- Why it matters: This specific mix can arise only in a very hot, dense universe for a short window of time. An eternal steady-state universe would not yield these proportions.

Cosmic Inflation: a Key Hypothesis (Still Under Test) #

In the 1980s, physicist Alan Guth introduced cosmic inflation: a phase of exponential expansion around 10⁻³⁶ to 10⁻³² seconds after the Big Bang, during which the universe’s volume grew by an enormous factor.

Why propose such an idea? Because the classical Big Bang struggles with several puzzles:

- Horizon problem: Without inflation, widely separated regions of today’s universe could never have been in contact — yet they share nearly identical properties, like temperature. Inflation explains this uniformity: before the extreme expansion, these regions were close enough to exchange information and energy.

- Flatness problem: Observations show that the universe is nearly flat (neither positively nor negatively curved). Without inflation, that would require extraordinarily precise initial conditions. Inflation acts as a flattening mechanism, driving space toward flatness on large scales.

- Monopole (and relic) problem: Grand Unified Theories predict magnetic monopoles produced just after the hot Big Bang. Without inflation, their present-day density would rival that of protons — we should see them everywhere. None has been detected despite intensive searches. Inflation dilutes such relics to undetectable levels.

- Origin of structure: Inflation also explains why the universe is not perfectly uniform. Tiny quantum fluctuations present before and during inflation were stretched to cosmological scales; these small density variations seeded galaxies and clusters.

Inflation is not yet definitively confirmed, but several of its predictions have left fingerprints in the CMB, especially in the fluctuation spectrum.

Implications of the Big Bang Theory #

In summary, the Big Bang model describes a universe emerging from an extremely hot, dense state — perhaps even a singularity in the sense of general relativity — followed by rapid expansion, with an inflationary phase potentially amplifying that initial growth. At such energies, general relativity and quantum mechanics together are insufficient: our description of the “instant zero” remains speculative, pending a theory of quantum gravity.

This scenario prevails because it explains a set of converging observations: the measured expansion of galaxies, the CMB and its blackbody spectrum, the primordial light-element abundances, and the emergence of large-scale structure.

The question of an absolute beginning, however, goes beyond physics and touches philosophy. Many scientists and thinkers, regardless of conviction, have expressed discomfort with a sharp beginning. Arthur Eddington, for example, wrote: “Philosophically, the notion of a beginning of the present order of Nature is repugnant to me.”

Why the resistance? Because for many, admitting a beginning suggests the existence of a first cause or a creative force. Section 3.3 will explore this link between a cosmic beginning and the idea of a first cause.

Alternative Theories #

Different alternatives to the Big Bang were proposed to restore an eternal universe.

The steady-state model was developed by British astronomer Fred Hoyle and colleagues in the 1940s. It posited an infinite, eternal universe while acknowledging expansion. To compensate for dilution as space expands, the model proposed continuous creation of matter, thereby avoiding any dense, hot primordial phase. For a time, this framework rivaled the Big Bang. It fell into disfavor mainly after the discovery of the CMB, which the steady-state model does not naturally explain.

Other competing models have been proposed:

Cyclic Universe (Big Bounce) #

General idea:

The bounce model2 proposes that our universe did not arise from a single Big Bang, but from an infinite series of oscillations: phases of expansion followed by contraction, repeated on cosmic timescales. In the distant past, the universe would have been far larger than it is today, then contracted over billions of years down to an extremely small — but never zero — size. Instead of collapsing into a singularity, it “bounced” and began a new expansion: the phase we observe today. In this framework the cosmos has no beginning and no end, existing from eternity.Theoretical versions:

- In loop quantum gravity, quantum-modified equations replace the singularity with a natural bounce once a critical density is reached.

- In some string-theoretic scenarios (ekpyrotic models or cyclic inflation), higher-dimensional membranes (branes) periodically collide, triggering cycles of contraction and expansion.

- These models sometimes impose a minimum contraction scale on the order of the Planck volume (~4 × 10^-105 m³), below which classical physics no longer applies.

Observational status:

- To date, there is no clear observational signature confirming previous cycles.

- Researchers hope to find hints in the CMB — e.g., anomalies or circular patterns that might betray a prior phase3.

- Other ideas include primordial gravitational-wave fossils or distinctive features in large-scale structure, but nothing conclusive has been detected so far.

- As one researcher quoted by Space.com summarized: “There is no empirical evidence today for bouncing cosmologies. But there is also no evidence for the initial singularity.”4

Theoretical limits and critiques2:

- Lack of empirical evidence: avoiding the initial singularity is appealing, but the bounce remains a “radical,” highly speculative hypothesis5.

- Less compelling than inflation: cosmic inflation remains the dominant framework because it robustly explains several puzzles (flatness, homogeneity, absence of magnetic monopoles, the observed CMB fluctuation spectrum).

- The entropy problem:

- The second law of thermodynamics requires entropy (overall disorder) to increase from one cycle to the next.

- Future cycles would thus grow longer and larger; past cycles would have been shorter and smaller.

- Pushed indefinitely into the past, this logic implies an initial cycle — undermining the claim of an eternal past without beginning.

- Proposed workarounds (no consensus):

- Quantum “entropy reset” at the bounce (suggested in some loop-quantum-gravity approaches).

- Exponential-expansion dilution as in Steinhardt–Turok models, which stretch entropy to near-negligible levels before the next cycle6.

- Two-arrow time: a bounce producing two opposite directions of time, each with its own increasing entropy.

- Conformal cyclic cosmology (Penrose): after vast timescales the far-future universe becomes ultra-dilute and radiation-dominated; this “scale-free” state is mathematically equivalent to a new beginning with low initial entropy7.

These scenarios are fascinating but remain highly speculative, with no observational confirmation yet.

Conclusion:

The Big Bounce offers an elegant, stimulating narrative that avoids the initial singularity. Nonetheless, it suffers from a serious lack of empirical support and faces major theoretical hurdles, especially entropy. Even if a bounce occurred, it remains far from clear that it escapes a beginning altogether: the existence of a first cycle or special initial condition still seems hard to avoid.

“Eternal” or “Emergent” Quantum Models #

General idea:

In these scenarios, the universe does not “begin” at a strict instant zero. It exists before the Big Bang as a quantum state (quantum vacuum, quasi-stationary state, Euclidean phase, etc.) and then emerges as a classical expanding universe. In other words, the Big Bang is not creatio ex nihilo but a phase transition.The quantum vacuum is not “nothing”:

In physics, “vacuum” means a lowest-energy state, roiled by quantum fluctuations that fleetingly create and annihilate particle pairs. This is far from the philosophical “nothing.” These models do not claim that the universe sprang from absolute nothingness.Common variants:

- Emergent universe: the cosmos remains for a very long time in a quasi-stationary quantum state (no true “t = 0”), then gradually enters a classical expansion phase.

- No-boundary proposal (Hartle–Hawking): there is no initial temporal “edge.” Classical time emerges from a quantum phase described by a wavefunction of the universe, thereby avoiding a singularity.

- Quantum tunneling (Vilenkin): the universe tunnels from a quantum (metastable vacuum) state into an expanding classical universe. Again, this is a transition, not a leap from absolute nothingness.

Limits and observational status:

These approaches remain highly speculative. They offer few distinct, easily testable predictions; any signatures tend to overlap with those of the standard model. As of today, no observation decisively selects one of these scenarios.

Conclusions #

Despite their conceptual appeal (eternity, singularity avoidance, etc.), alternative models struggle to reproduce all observations simultaneously. The steady-state model is largely ruled out by the CMB; cyclic/bounce and “eternal” quantum models remain intriguing but lack distinctive, confirmed signatures.

Discoveries Leading to Cold Dark Matter (CDM) and Dark Energy (Λ) #

Since the late 1970s, it has become clear that a hot, dense Big Bang alone cannot explain everything we observe. In galaxies, stars in the outskirts orbit too fast to be accounted for by luminous matter alone; in clusters, the mass inferred from galaxy motions, hot X-ray gas, and gravitational lensing far exceeds the visible mass. On cosmological scales, the high-precision CMB maps show that additional matter is needed to form the observed large-scale structure. The simplest solution is to posit an additional, invisible component that was dynamically “cold” in the early universe: cold dark matter. It emits little or no light, interacts mainly via gravity, and provides the scaffolding for filaments, galaxies, and clusters.

Then came the 1998 surprise: distant supernovae appeared dimmer than expected, implying that the universe’s expansion is accelerating. Meanwhile, CMB measurements indicate a nearly flat geometry. Reconciling flatness with accelerated expansion requires a component with negative pressure that drives space to expand faster over time: dark energy, most simply modeled by the cosmological constant Λ. Combining supernovae, baryon acoustic oscillations (BAO), and the CMB yields a coherent picture: roughly 5% baryons, ~25% cold dark matter, and ~70% dark energy — the ΛCDM model.

Are there dissenting views? Yes. To replace dark matter, some modify gravity (MOND and extensions like TeVeS): these can fit certain galaxy rotation curves, but struggle with other tests (e.g., cluster dynamics and CMB maps). For dark energy, others alter gravity at large scales (e.g., f(R) theories, back-reaction scenarios) or allow time-evolving dark energy; these avenues are under study but, taken together, do not outperform the simple Λ explanation across all datasets.

Tensions remain — notably the current expansion rate H₀ and the growth of structure (σ₈/S₈). These keep questions open and drive ever-tighter tests of ΛCDM. For now, however, cold dark matter and dark energy remain the most effective ingredients to explain, all at once, internal system dynamics, the universe’s geometry, and its expansion history.

The Latest Findings (After Λ and CDM) #

With ΛCDM in place, cosmology entered an era of high-precision measurement. CMB maps — first with WMAP and especially with Planck — refined key parameters (age, matter/energy content, near-zero curvature) and confirmed the model’s overall coherence. Ground-based experiments like ACT and SPT extended these measurements to smaller angular scales, providing independent checks and complementary constraints.

In parallel, large galaxy surveys have revealed the imprint of baryon acoustic oscillations, a true standard ruler for reconstructing the expansion history. Combined with weak gravitational lensing (KiDS, DES, HSC), these 3D maps have tracked the growth of structure, tested gravity on large scales, and strengthened the picture of a universe structured by cold dark matter. More recently, the James Webb Space Telescope has found very early galaxies — sometimes more massive or luminous than expected — prompting refinements to models of star formation and galaxy assembly, without overturning the standard framework.

These advances have not erased all questions. The value of H₀ differs depending on whether it is measured locally (Cepheids + supernovae, masers, strong lenses) or inferred from the CMB under ΛCDM; likewise, some indicators of structure growth hint at a mild tension. Such discrepancies may reflect still-uncontrolled systematics, or they may point to new physics. Upcoming datasets — DESI (underway), Euclid, and soon the Rubin Observatory — should clarify the magnitude of these tensions and, depending on the outcome, either bolster the model or guide its evolution.

What Next? #

The current cosmological model is not fixed in stone: it is built from available data, makes quantitative predictions, and is tested by new observations. When results fail to fit, the model is revised. This cycle — observe → model → predict → test → revise — lies at the heart of progress in cosmology.

- Observe → Model. Early expansion measurements led to a dynamic universe; plasma physics in the primordial era suggested a hot, dense state.

- Model → Predict. Before 1965, a microwave fossil background was predicted — and later detected by Penzias & Wilson. In the 1980s, inflation was introduced to solve horizon/flatness problems; it predicts nearly scale-invariant, adiabatic, (quasi)-Gaussian fluctuations, later confirmed by WMAP/Planck. In 1998, Type Ia SNe revealed acceleration: Λ (dark energy) was added; BAO, CMB, and lensing converged on a consistent parameter set.

- Test → Revise. Today, tensions (H₀, σ₈/S₈) and surprises (very early, bright JWST galaxies) drive refinements in astrophysics and analysis — or motivate extensions of the standard framework if needed. Knowledge evolves: the model adjusts in light of the best data.

Takeaway: ΛCDM is a predictive tool that has passed many tests (expansion, CMB, BAO, light elements, structures), yet it remains revisable. Precisely because it makes sharp predictions, it can be confirmed — or challenged — and thus improved.

Every model rests on assumptions. To assess how far ΛCDM applies, and where it must be adjusted, those assumptions should be made explicit and tested.

Underlying Assumptions

As Jean-Philippe Uzan notes in POUR LA SCIENCE No. 5218, cosmologists build the Big Bang model upon a set of assumptions that should be continually scrutinized. As measurements become more precise, are these assumptions — and the model itself — still adequate for interpreting observations? Should some be dropped or modified? Remember: any model is a working tool, a temporary consensus — necessarily limited and open to revision.

Stepping back, four major assumptions stand out, which we label H1–H4:

- H1: Gravity is accurately described by general relativity.

Mathematically, spacetime geometry is determined by Einstein’s equations. - H2: Matter and its non-gravitational interactions (electromagnetic, strong and weak nuclear) are described by the Standard Model of particle physics, grounded in quantum physics.

- H3: The universe is homogeneous and isotropic on large scales.

We do not occupy a special place (Copernican principle); the portion we observe is representative of the whole. H3 sets the local geometry of the universe: spatial matter distribution is homogeneous, expansion is the same in all directions and at all points — though it may change over time. - H4: The universe has no exotic large-scale structure beyond what has been observed.

No extreme inhomogeneities/an-isotropies or exotic topology dominating on scales larger than currently detected.

These are not absolute truths; they must be constantly tested against new observations. Like any scientific model, the Big Bang framework will evolve. For now, it remains the most coherent and predictive theory for explaining the universe we observe, even if it exhibits internal limits and tensions (e.g., the Hubble constant and the nature of dark energy).

Conclusions #

Two principal features of the observable universe are its large-scale homogeneity and isotropy and its expansion. Cosmology’s aim is to propose a model that describes such a universe and explains the structures that formed within it. At present, the Big Bang model is the best way to organize, coherently and rationally, the knowledge we have amassed about the universe and its history, and it is confirmed by the most recent observations.

The atheist philosopher Antony Flew commented on this point (in There Is a God: How the World’s Most Notorious Atheist Changed His Mind 9):

It is now widely accepted that the universe had a beginning. This is something that seems to support the claim that the universe was brought into existence by a creative intelligence. As a philosopher, I find this conclusion deeply troubling. For a long time, it was convenient to assume that the universe had always existed. But the Big Bang theory has changed that. It now seems that the cosmologists are proving what Saint Thomas tried to prove philosophically — that the universe had a beginning.

Further Reading #

Andrew May, with contributions from Daisy Dobrijevic (2025). What is the Big Bang Theory? Link: https://www.space.com/25126-big-bang-theory.html ↩︎

James Riordon (2023). The Universe Began with a Bang, Not a Bounce, New Studies Find. Link: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-universe-began-with-a-bang-not-a-bounce-new-studies-find/ ↩︎ ↩︎

Penrose, R. (2010). Cycles of Time: An Extraordinary New View of the Universe. ↩︎

Tereza Pultarova (2017). “What If the Big Bang Wasn’t the Beginning? New Study Proposes Alternative.” Link: https://www.space.com/38982-no-big-bang-bouncing-cosmology-theory.html ↩︎

Was the Big Bang Really a Big Bounce? — Columbia Magazine (2019). Link: https://magazine.columbia.edu/article/was-big-bang-really-big-bounce ↩︎

Steinhardt, P. J., & Turok, N. (2002). A Cyclic Model of the Universe. Science. ↩︎

Penrose, R. (2005). The Road to Reality. ↩︎

Jean-Philippe Uzan (2021). Tester les fondements du modèle du Big Bang, POUR LA SCIENCE No. 521. Link: https://www.pourlascience.fr/sd/cosmologie/tester-les-fondements-du-modele-du-big-bang-20871.php ↩︎

Antony Flew (2007). There Is a God: How the World’s Most Notorious Atheist Changed His Mind, HarperOne. ↩︎