2. Approaching the Spiritual Quest Scientifically?

Even what seems most concrete, rational, and undeniable — like mathematics — ultimately rests on assumptions. Any proven statement takes the form: if we assume XX, then we can prove YY through reasoning (even if the assumptions are not always stated explicitly). These basic assumptions are called axioms.

According to the Larousse dictionary, an axiom is:

- In Aristotelian logic, the starting point of reasoning, considered self-evident and not demonstrable.

- The initial statement of an axiomatized theory, serving as the foundation for further demonstrations.

- An unquestioned proposition, accepted as the basis of an intellectual, social, or moral framework — a truth admitted by all without discussion.

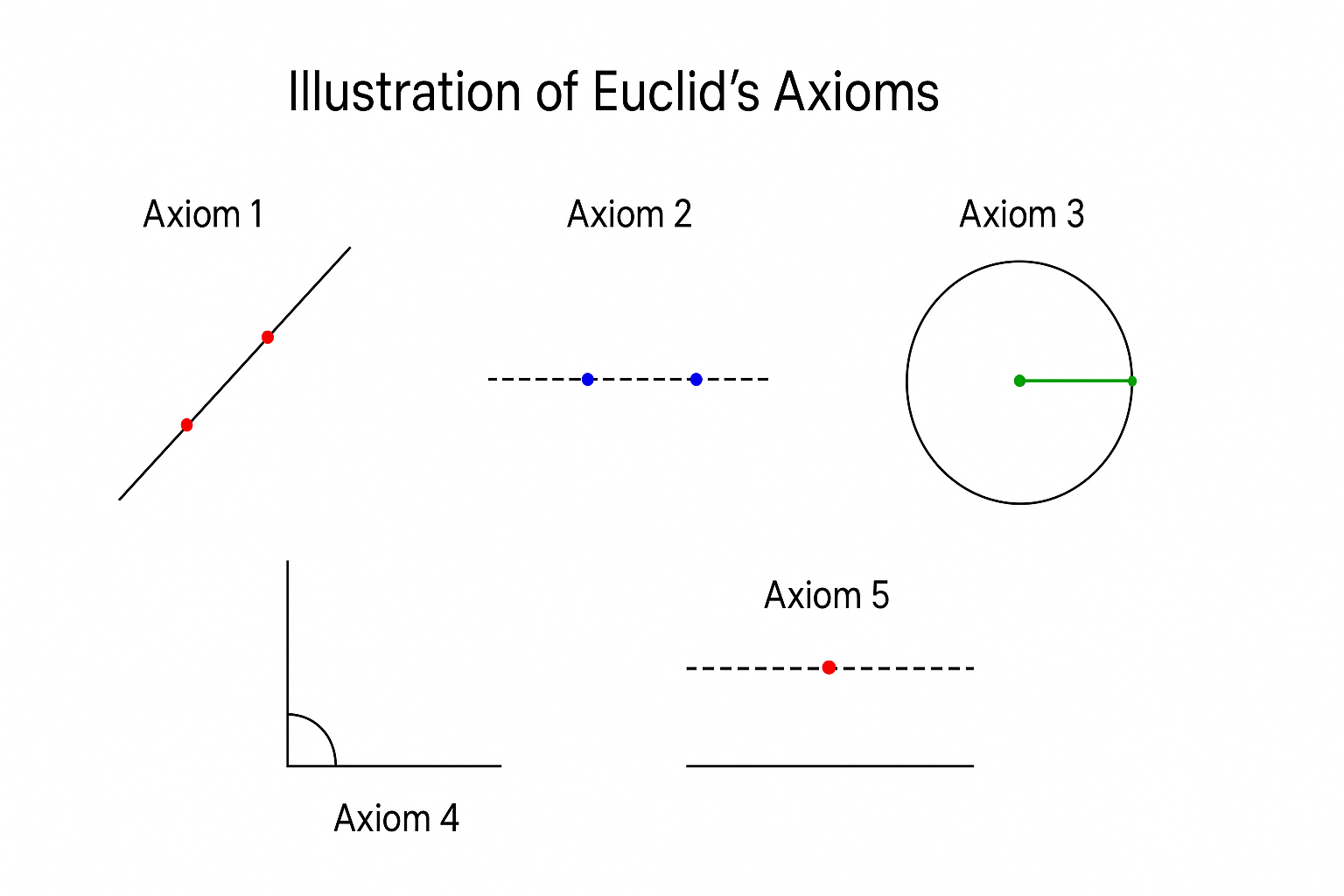

For example, Euclidean plane geometry (geometry on a flat surface, like a sheet of paper) is built on five axioms, known as Euclid’s postulates ( bibmath.net):

- Through any two points, there is always a straight line.

- Any line segment can be extended indefinitely in a straight line.

- From a given segment, one can construct a circle whose center is at one endpoint and whose radius is the length of the segment.

- All right angles are equal to one another.

- Given a point and a line not passing through it, there exists exactly one line parallel to the first that passes through the point (the parallel postulate).

These statements are easy to verify in practice — for instance, if you mark two points on a page, you can easily draw a straight line through them with a ruler. But formally proving them is impossible.

From these axioms, the rest of plane geometry can be deduced and demonstrated. For example, the parallel postulate leads to the conclusion that the angles of a triangle always sum to 180 degrees.

This shows that nothing is absolutely provable — not even mathematics. It, too, rests on assumptions, whether explicit or implicit. In this sense, everything is relative. The same is true for the sciences: physics, cosmology, biology, even medicine.

Take clinical trials, for instance. When a study shows that a drug outperforms a placebo, the conclusion relies on statistical methods. Even here, results come with a margin of error. A common threshold is p < 0.05 — meaning there is still a 5% chance that the observed effect is due to random variation, that patients improved by chance rather than because the drug worked. Beyond this, results rest on underlying assumptions, such as:

- That participants are representative of the general population,

- That the measurements used (e.g., symptom scores) are valid and reliable,

- That the observed effect truly comes from the drug, not from uncontrolled biases (like expectation effects, measurement errors, or contextual factors),

- That the chosen statistical analyses are appropriate for the data.

In other words, even a “significant” result is never absolute proof. It is a probabilistic conclusion, valid only within a well-designed methodological framework.

Scientific theories — from atomic models to the laws of gravity — work the same way. They aim to best explain observations, but they too rest on assumptions, have limitations, and evolve as new discoveries emerge.

The scientific method does not use the verb 'to believe'; science merely proposes provisional explanatory models of reality, ready to be revised as soon as new information contradicts them.

A theory is not disproven simply because certain observations seem inconsistent with it. It only means the theory cannot explain everything. Like us, it has limits.

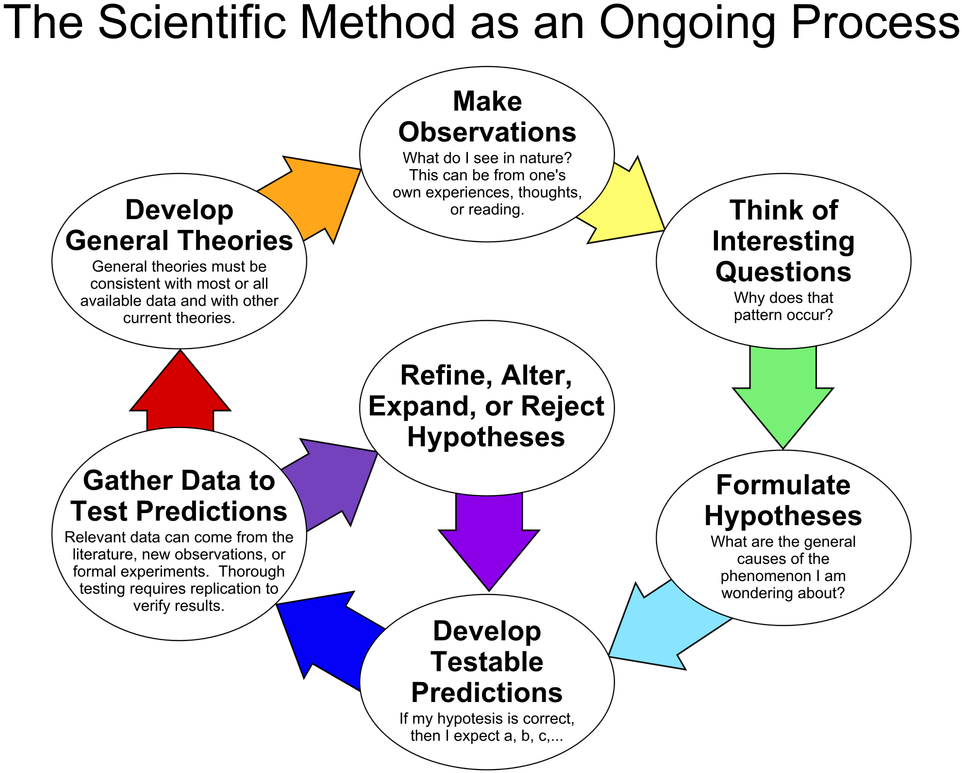

The scientific method generally follows these steps:

- Observe a phenomenon: What is happening in nature? Observations may come from experience, reflection, or research.

- Ask meaningful questions: Why does this phenomenon occur? What factors influence it?

- Formulate a theory (with its assumptions/axioms) to explain the phenomenon.

- Make testable predictions: If my theory is correct, I should observe X, Y, Z…

- Experiment and collect data:

- Data may come from studies, observations, or controlled experiments.

- For validity, results must be reproducible.

- Analyze results and adjust the theory if needed: Do the findings support the hypothesis, or must it be revised?

- Develop a general theory: A scientific theory should be consistent with most available data and compatible with other established theories.

In this blog, I propose to explore the question of God’s existence using an approach inspired by the scientific method. The goal is not to prove the existence of God scientifically — which would be impossible, since God is not a physical, measurable, or directly observable phenomenon. However, if God does exist, it is reasonable to ask what effects such an existence might have on the world.

This reflection will therefore proceed in that spirit: by gathering information from different sources, examining which hypotheses best account for the greatest number of observable elements, and identifying those that appear the most coherent, rational, and reasonable.

As in science or mathematics, this approach rests on certain intuitively sensible starting principles — comparable to Euclid’s axioms in geometry — which cannot be proven in themselves, but from which it becomes possible to build an understanding of reality and to draw conclusions.

I therefore propose to examine the different sources of evidence, to formulate these foundational hypotheses, and then to explore their implications. This inquiry will remain open-ended: it may evolve in light of new experiences, discoveries, or information, just as scientific research does.